July 6, 2022 @ 7:00 pm – 8:30 pm

Headstrong heroines and hot-tempered chieftains, loch monsters and hill fairies, cattle raids and clan feuds, wise animals and foolish saints: the folktales of the Scottish Highlands preserve the history and beliefs of a people deeply rooted in their land and culture.

The fairy hill can be understood in Gaelic tradition not just as the portal to the Otherworld, but as the gateway of the imagination. Highland exiles from the Clearances carried these tales and traditions with them – most notably to Nova Scotia, where Gaelic storytelling has survived to the present.

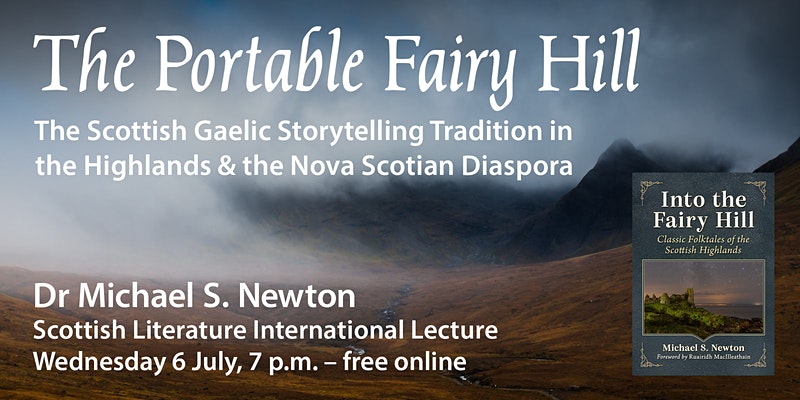

This talk will offer an overview of the Gaelic storytelling tradition in Scotland and Nova Scotia, some of the masterpieces of this verbal art, and what it tells us about Gaelic cultural values and identity.

All welcome!

Dr Michael S. Newton was an assistant professor in the Celtic Studies department of St Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia from 2008 to 2013. He has written a multitude of books and articles about Gaelic culture and history and is a leading authority on Scottish Gaelic heritage in North America. His anthology Into the Fairy Hill: Classic Folktales of the Scottish Highlands will be published later this year by McFarland. He lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

This event will be run via Zoom. Login details for the event will be sent out by email on Tuesday 5 July. ASL gratefully acknowledges the support of the Scottish Government in presenting this lecture.